calsfoundation@cals.org

Dropping History Is Impossible

I recently had a student of mine, from when I was doing some adjunct teaching at the University of Arkansas Clinton School for Public Service, contact me regarding the possibility of her going back to school, this time for a PhD. What could I tell her about the program I myself attended? I could tell her plenty, but I was honestly concerned about her expectations. Right now, universities are producing far more PhDs than there are full-time jobs requiring such a degree. The latest American Historical Association jobs report noted that the number of tenure-track positions advertised from June 2020 to May 2021 had fallen to an all-time low of 167. Over that same time period, universities probably cranked out ten times that number of PhDs. The job market is getting so bad that even Yale University has warned its prospective doctoral students that maybe only half of those studying at one of the most prestigious institutions in the United States, if not the world could expect an offer of full-time employment somewhere upon graduation.

There are all kinds of reasons for this. The ongoing pandemic has played its part in disrupting the operations of higher education. The growth of the college-educated population has resulted in a feedback loop of people who automatically turn to college and expect to find a job commensurate with their studies upon graduation, not considering other avenues for employment. This has led to universities downplaying the traditional “liberal arts” background in order to focus upon more allegedly employable endeavors, especially STEM-related fields. Even the classic World Civ or American History survey courses are being cut to allow the customers of the modern university to start building their job skills right off the bat.

There are all kinds of reasons for this. The ongoing pandemic has played its part in disrupting the operations of higher education. The growth of the college-educated population has resulted in a feedback loop of people who automatically turn to college and expect to find a job commensurate with their studies upon graduation, not considering other avenues for employment. This has led to universities downplaying the traditional “liberal arts” background in order to focus upon more allegedly employable endeavors, especially STEM-related fields. Even the classic World Civ or American History survey courses are being cut to allow the customers of the modern university to start building their job skills right off the bat.

We can debate the merits of this—many have. If you think that it’s important for someone to have a background in “the classics,” then ask yourself what those folks who lived during that time of “the classics” were themselves studying. Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle were trying to solve the problems that faced them at the time and had no idea that they were to lay the rhetorical and conceptual groundwork for much of our world. Conversely, during large swaths of Chinese history, people studied the writings of Confucius closely primarily because one had to pass a test on them in order to get a good-paying government job. The meaning, value, and purpose of education regularly shifts over time, and the downplaying of history has, itself, a long history.

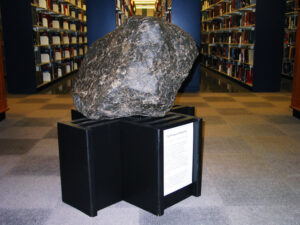

Of course, we’ve cut out history here, too, although only in name. When we redesigned the EOA the first time some years back, we changed the title slightly, dropping the “History & Culture” portion of the name, so that the site became simply the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. This was done in part because the website had originally been copyrighted under the shorter name, but also because we felt that the scope of the EOA had expanded pretty far beyond history, including such subjects as meteorites and slime molds and millipedes. It seemed that dropping “History & Culture” from our name was the best way to acknowledge our expanded scope.

But now, I think that the word “history” maybe encompasses that expanded scope. At least, that’s what the philosopher R. G. Collingwood argued back in his posthumously published 1945 book The Idea of Nature. After surveying how the conception of nature has been predicated, in different points in time, upon the ancient Greek “theory of forms,” the post-Renaissance obsession with mechanical devices, and the nineteenth-century promulgation of evolutionary theory, Collingwood asks the question: “Where do we go from here?” And for a philosopher who has just spend more than 170 pages tracking important shifts in the natural sciences, his conclusion is surprising but also so compelling that it is worth quoting here at length:

Natural science (I assume for the moment that the positivistic account of it is at least correct so far as it goes) consists of facts and theories. A scientific fact is an event in the world of nature. A scientific theory is an hypothesis about that event, which further events verify or disprove. An event in the world of nature becomes important for the natural scientist only on condition that it is observed. “The fact that the event has happened” is a phrase in the vocabulary of natural science which means “the fact that the event has been observed.” That is to say, has been observed by someone at some time under some condition; the observer must be a trustworthy observer and the conditions must be of such a kind as to permit trustworthy observations to be made. And lastly, but not least, the observer must have recorded his observation in such a way that knowledge of what he has observed is public property. The scientist who wishes to know that such an event has taken place in the world of nature can know this only by consulting the record left by the observer and interpreting it, subject to certain rules, in such a way as to satisfy himself that the man whose work it records really did observe what he professes to have observed. This consultation and interpretation of records is the characteristic feature of historical work. Every scientist who says that Newton observed the effect of a prism on sunlight, or that Adams saw Neptune, or that Pasteur observed that grape-juice played upon by air raised to a certain temperature underwent no fermentation, is talking history. The facts first observed by Newton, Adams, and Pasteur have since then been observed by others; but every scientist who says that light is split up by the prism or that Neptune exists or that fermentation is prevented by a certain degree of heat is still talking history: he is talking about the whole class of historical facts which are occasions on which someone has made these observations. Thus a “scientific fact” is a class of historical facts; and no one can understand what a scientific fact is unless he understands enough about the theory of history to understand what an historical fact is.

Look at what Collingwood is doing here. I remember in junior high and high school going through the process by which scientific knowledge is built, starting from observations through hypothesis and experimentation, sometimes to be repeated and repeated, but I never thought of this as a process of history, of scientific facts being predicated upon historical facts. As I wrote in a previous blog post, “More than anything else, history is the critical interpretation of surviving sources of information detailing what happened in the past.” But science is also the critical interpretation of surviving sources of historical information. Those observations that started the application of our scientific method to solve this or that problem—well, they had to be recorded. The hypothesis had to be recorded in a way that could be transmitted, and the effects of the experiment had to be recorded. Scientific knowledge is passed down as historical sources. Moreover, some of the debates we have about the trustworthiness of sources of scientific information (did they actually observe that phenomenon?) are the same debates we have about the trustworthiness of sources of historical information (did they actually observe that event?).

Collingwood goes on to write:

The same is true of theories. A scientific theory not only rests on certain historical facts and is verified or disproved by certain other historical facts; it is itself an historical fact, namely, the fact that someone has propounded or accepted, verified or disproved, that theory. If we want to know, for example, what the classical theory of gravitation is, we must look into the records of Newton’s thinking and interpret them: and this is historical research.

Here, I would like to note that it is not only historians who must occasionally rush to the archives. Natural history museums across the planet serve as repositories of species samples or bones or minerals and ores. Occasionally, a new theory demands revisiting old fossils to determine if this theory might hold true, but those fossils are only as valuable as the information regarding their provenance—that is, information about their history.

In his final paragraph, Collinwood looks forward thusly:

I conclude that natural science as a form of thought exists and always has existed in a context of history, and depends on historical thought for its existence. From this I venture to infer that no one can understand natural science unless he understands history: and that no one can answer the question what nature is unless he knows what history is. This is a question which Alexander and Whitehead have not asked. And that is why I answer the question, “Where do we go from here?” by saying, “We go from the idea of nature to the idea of history.”

In other words, the tools of historical investigation are woven into the very fabric of scientific inquiry. There are good reasons to worry that many in our society are not sufficiently schooled in the history of their own country, their own state, but history as a discipline will not die out, cannot die out, so long as any kind of intellectual inquiry is taking place. The idea of history is embedded in the STEM fields that are so often touted as the replacement of the humanities. History does not hold us back. History is the only thing that can move us forward.

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas