calsfoundation@cals.org

“Just the Facts”? Oral History in Pursuit of a Dialogue

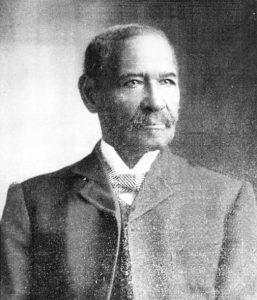

On Saturday, I had the privilege of addressing the Dunbar Historic Neighborhood Association’s annual community festival. Last year, the festival took place in the Sue Cowan Williams Library parking lot, but this year, for obvious reasons, it was held virtually. As part of the “Dunbar Historic Moments” portion of the program, I presented a very brief overview of Herbert Denton Jr.’s journalistic career, with the conclusion that he just might be the most significant witness to history ever to come out of Little Rock, Arkansas.

My summary of Denton’s professional biography touched on one of the major themes that I raised in my last Butler Banner blog post: the Dunbar neighborhood’s love of learning and expectations of excellence. In my presentation, I noted that Denton’s legacy at the newspaper—“his uncanny eye for spotting individual potential and developing individual talent,” by which he “quietly became one of the greatest forces of desegregation in the Washington Post newsroom”—was “a testament to his Dunbar–Little Rock roots.”

I also noted my belief that, upon arriving in Toronto in 1985 as the Washington Post’s first ever Canada bureau chief, Herb Denton must have “recognized and appreciated the fullness of the circle: He was ending up in the country whose first Black elected official, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, was the namesake of his own elementary school—as well as his father’s high school, the forerunner to Dunbar—back in Little Rock, where Mr. Gibbs himself had ended up.” (Gibbs was elected to the Victoria City Council in 1866, actually making him the second Black elected official in Canadian history, and the first in British Columbia; that doesn’t take anything away from his achievement or the inspiration that I’m sure both Herbert Junior and his father drew from him.)

In 1958, because of the Lost Year in Little Rock public schooling, Herbert Denton Jr. left Little Rock and never returned except to visit family. He was fifteen. As he went first to the Windsor Mountain boarding school in Lenox, Massachusetts, and then to that most rarified of American colleges—Harvard—he exuded what one of his friends termed for me, in retrospect, “that Little Rock mystique.”

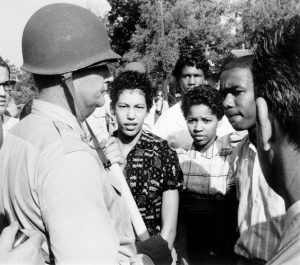

What was that Little Rock mystique? It’s difficult to say, exactly. Of course, the moral leadership of the Little Rock Nine thrust that mystique into our national consciousness, but I think there is much more beneath the surface of their singular example. (Not to mention the woeful fact that Americans of my generation are, generally speaking, much less aware of their story than our parents and grandparents are.) For me, oral history interviews have played a crucial role in cultivating the appropriate approach to understanding Little Rock’s distinctiveness, as it relates to the life of Herbert Denton Jr. Such cultivation is a lifelong process.

***

In January 2019, I asked a version of the Little Rock–mystique question—“It seems like there’s something really special about Little Rock on the map of Black America…but I can’t quite put my finger on it”—to Dr. Charles Denton Johnson, a professor of public history at North Carolina Central University. Dr. Johnson’s mother, Carolyn Denton, was Herbert Denton Jr.’s first cousin. She also grew up down the street from Dunbar, in her uncle Herbert Denton Sr.’s “sphere of protection and influence,” as Dr. Johnson described it, and, among other things, went on to become the first Black woman elected to the City Council of Durham, North Carolina.

Dr. Johnson’s response to my question is worth reproducing at length. He began by noting that his mother “thought the world” of having gone to both Gibbs Elementary and Dunbar High School in the 1930s and ’40s; thanks to the Denton influence, she indeed considered Little Rock to be a special place. But then, Dr. Johnson proceeded to both nuance and broaden the terms of my question.

“For African Americans,” he said, “an aspect of our history is the importance of place. Each community is, in its own way, very special. And I would say people have sort of this—it’s almost like their living community is a personal fable, if you will. Their community is special and unique, and it is. It really is. But if you went to other places—you know, Memphis, you come to Durham, you go to Richmond, you know, Atlanta, New Orleans—I mean, people will be talking about it. I guess for you, it’s to figure out how to distill, like, ‘Well, what is it about the Little Rock thing?’ You know?…You’re going to have to keep digging. And I think it will come out as you talk to different relatives about that, and kind of get a sense. And not just relatives. I mean, other people, the African Americans in that area, should be able to help give you a sense of that….I think, to me, part of your task will be to get a real sense of what made Little Rock, for Blacks, Little Rock. What was its je ne sais quoi, you know what I mean?”

***

Seven months later, when I began my official affiliation with CALS, my hope was that the Herbert Denton Community History Project might serve as a venue for gathering and synthesizing many different takes on Little Rock’s je ne sais quoi. I envisioned a large-scale, community-centered oral history project, which might produce an archive of Black Little Rock life histories, not unlike the seminal Joel Buchanan Archive of African American Oral History (a collection of 700+ interviews representing Black Florida life histories) that I had seen unveiled at the University of Florida earlier that spring. I imagined such a project could depend on a dedicated cohort of volunteer oral historians, whom I would train at CALS branches. As an extension of my quest to understand and represent Herbert Denton Jr.’s foundations in their fullness, I saw this as a tremendous win-win-win opportunity for my project, for present-day Little Rock, and for future generations of Herb’s home folks.

But I’ll be honest. It’s been difficult to pursue both of these projects—writing a full-life biography on one hand, and facilitating collaborative community history on the other—simultaneously. I spent most of the fall of 2019 in other places, attending the Oral History Association annual meeting and conducting interviews with Herbert Junior’s journalistic colleagues. And I was quickly forced to remember just how much work goes into designing and executing a volunteer-driven oral history project. Such efforts should not be undertaken casually.

At the start of this year, I finally signed a year-long lease here, and started to settle into a Little Rock groove. I began teaching UA Little Rock’s master’s level oral history course, helped the folks at the CALS Roberts Library prepare oral history recorder kits for circulation in CALS branches, and gave a Legacies & Lunch talk in February that used Herb Denton’s own incisive 1982 essay, “The Deeper Dilemmas of Little Rock,” as a means of framing the intergenerational dialogue that I hoped—and still hope!—the Herbert Denton Community History Project might help foster in Herb’s hometown.

Then, of course, the pandemic hit, and things got waylaid. And yet, in some ways, it’s been a blessing in disguise for me. The twelve consecutive months I’ve spent here are the longest I’ve ever stayed in one place since college. Being “forced to sit down,” as I often explain it to my friends, gave me a lot of time to read; to conduct interviews with Denton’s colleagues over Zoom and the phone; and to slowly process not only a lot of research-related information, but also some of the deep, personal underpinnings of my work as an oral historian, as Herb’s biographer, and as a relatively young, brown, first-generation American who is seeking to activate the lessons of Little Rock’s Black lives for those who come up in this country alongside and after me.

***

One interview that I conducted at the end of this summer really helped me crystalize these reflections, which are continuing to shape my imagination of the Herbert Denton Community Project.

The interview took place over Zoom. It was with Edward Moore Jr., who grew up next door to the Denton family on Pulaski Street. Only a couple years younger than Herbert Junior, Mr. Moore is himself one of Little Rock’s most distinguished sons, having risen to the rank of vice admiral in the United States Navy, the highest position ever held by an African American in that branch of the military.

Our interview lasted almost three hours. I (along with my older brother Nate, who has been working as a researcher on the biography project) asked many questions, some quite probing, about the childhood environment that Moore shared with Herbert Junior. Toward the end of our conversation, Moore gave me the gift of eye-opening advice for future interviews.

“If you’re trying to get at the personal level, to inform who Herb was and how he reacted to his environment and his situation and his times, and what shaped his worldview, and that reaction, that can be tough to tease out,” Moore told me. “Not because people are necessarily reluctant to talk about them, but because many of the memories are personally painful. You bury those things; you haven’t thought about them for a long time….So even the discussions that we’ve had with you, and other discussions that have been held that are similar to that, where someone says, ‘Tell me how it was, back in the day, so that I can understand your worldview, your perspective, where you’re coming from—sometimes you’re not going to get the straight skinny—what we call in the navy the ‘straight story,’ the ‘straight skinny’—or the whole story. Not that people are purposely lying to you, but you have to recognize that you might be delving into something that has been repressed, suppressed, and is personally painful to relive. The Little Rock desegregation crisis can be viewed in a detached way only so far by the people who lived it….It’s going to be difficult to tease a lot of what you’re trying to get out in a—not necessarily a truthful way, but in a realistic and revelatory way.”

Moore’s advice then became an even more precious gift: direct and constructive feedback on my oral history interviewing technique. “I’ve noticed you have a tendency to dive right in and ask questions from a [place of], you know, ‘I’m just trying to get at reality and the truth here.’…I don’t mean this in a negative way,” he went on, “but you definitely have a Jack Webb kind of approach.”

“I don’t know what that is,” I confessed. “What’s a jackweb?”

Mr. Moore chuckled, and then suggested we “dredge up some old Dragnet episodes,” so that I might observe the interviewing style of “Jack Webb and his trusty partner.”

“Webb is all business,” Moore explained. “And when he knocks on the door, you know, his questions are direct, to the point, and his famous statement is, ‘Just the facts, ma’am. Just the facts.’ And he says it in this very pointed way, like, ‘I just want the truth, I just want the facts, I just want to get at the meat right now!’”

Moore laughed, then continued, “When you’re interviewing older adults, they’re going to have a frame of reference that sort of categorizes you as a Jack Webb type….Some people are going to be resistant to giving you ‘just the facts’ in the way that gets at and informs where you think you are going with this story. So be open to it, be open to it, is all I’m saying.”

Although I still need to watch Dragnet, I often think about what Moore communicated to me. Participants in the “Oral History at Home” workshops that I teach monthly at CALS (the next one is actually today at 2:00 p.m.!) will tell you that dialogue—underpinned by an attentiveness to shared authority—is the foundational structure of an oral history interview. So to realize that I had fallen short of that aspiration, or at least failed to sufficiently humanize myself as a partner in the dialogue, was a humbling and important experience for me. It was a reminder that there is so much more to this work than mere research imperatives, a process of digging for pure information. As Moore said, what I’m really after are memories. Oral historians should never forget, and never fail to communicate, that memories are the stuff of human souls and community bonds. We need to treat them as such.

As the new year approaches, I want to make good on my own intention to do something in Little Rock, about Little Rock, and above all with Little Rock, that Herb Denton himself would be proud of. Herb didn’t write often about his hometown, but when he did, his words offered incisive assessments of both the challenges that faced Black Little Rockians of his generation, and their efforts—both organized and individual—to overcome them. So I’m going to start taking some deeper cues from that work.

In my next post, the third and last of this series, I will survey the five articles that Herbert Denton Jr. published about Little Rock in his lifetime. My hope is that, in the next seven months (and hopefully beyond), the Herbert Denton Community History Project might facilitate some sensitive, invigorating, and really useful discussions about the central and abiding questions raised in these pieces. How have these questions been dealt with? In what ways do they remain with us, perhaps in new forms? And how might they prepare us for the stony roads ahead?

Stay tuned for my third and final piece in the weeks to come, and soon after that we’ll begin the dialogue.

By Benji de la Piedra, director of the Herbert Denton Community History Project, Central Arkansas Library System