calsfoundation@cals.org

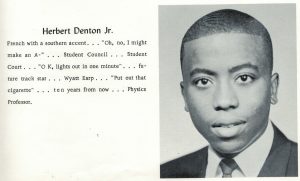

The Abiding Challenge of Integration: Herbert Denton Jr. and the Deeper Dilemmas of Little Rock

On the afternoon of April 27, 2016, I started my first drive from Washington DC to Little Rock. That same day, the Atlantic published a long feature article, written by Alana Semuels, about my destination: “How Segregation Has Persisted in Little Rock.” I remember a friend texting me the link the next day, when I was stopped at a gas station somewhere in Tennessee.

In many ways, some of which I can only appreciate in retrospect, Semuels’s reporting set the tone for my own effort to understand Little Rock as the place where Herbert Denton Jr.’s values and personality first took shape.

Semuels’s article began with the story of LaVerne Bell-Tolliver integrating Forest Heights Junior High in 1961. After briefly listing some of the traumatic challenges that Bell-Tolliver faced there, Semuels reported that “Bell-Tolliver looks at Little Rock schools now, though, and wonders if her years of hell were all in vain. In the decades since the schools were first integrated, Little Rock has become a more residentially segregated city.…Because the vast majority of children attend schools in their neighborhood, the schools have become re-segregated too.”

Perhaps because I was looking to orient myself to a place that I had never been before, the part that I remembered (and still remember) the most was this: “Little Rock is predominantly a black and poor city to the south of I-630, but it’s a white and affluent town north of I-630 and west of I-430, [John] Kirk told me….The borders of Little Rock look like the head of a bird facing east; the face and beak are majority black, while the feathers on the top of its head are mostly white.”

Unfortunately, the very next paragraph—which offered a crucial explanation for this state of affairs—did not sink in as deeply for me. It would take me several conversations and oral history interviews with longtime Little Rockians that summer to learn the history that Semuels wrote about, and only now as I write this Butler Banner blog post am I fully appreciating what she wrote: “That segregation came about intentionally, Kirk says, beginning in the 1950s. Whites and blacks once lived in proximity to one another, he said, until the Federal Housing Act of 1949 was passed. That law allowed the city to replace dilapidated housing, and permitted planners to tear down a black neighborhood close to the town’s relatively white center. The city then constructed public housing for black families in the city’s far east side, he said, while the state built highways to speed white residents’ exodus to the western suburbs. Highway I-630, like many throughout the country, was built on top of where a vibrant black community had thrived, and in constructing it, the state decimated that neighborhood while putting up a boundary that segregated the city.”

***

I am reminded of this article now because I recently discovered an uncannily resonant story, written almost fifty years prior, by Herbert Denton Jr. His story appeared on page A2 of the Washington Post’s Sunday, February 2, 1969, edition, under the headline, “Race Issue Still Dogs Schools in Nation, Conference Told.”

Reporting on a national gathering of 100 Black school board members from thirty different states, Denton began his article as follows: “Nobody wants to repeat 1957, when Army troops were sent to Little Rock (Ark.) Central High School to enforce a court desegregation order. School integration, nevertheless, remains the chief issue facing Little Rock’s schools, T.E. Patterson, the only Negro on the city’s seven-man school board, said yesterday.”

In keeping with the traditional journalistic ethos, Denton (who by then had been working the Post’s education beat for about six months) did not discuss his own proximity to the Central High crisis, which unfolded a mile away from his house during his ninth-grade year at Dunbar Junior High. In fact, he did not disclose his Little Rock roots at all in this article. (Again, par for the journalistic course.) Instead, he kept the focus on Patterson, who explained to this conference that, “as demands have broadened from a token to a wider integration of [Little Rock] schools, conservatives have been reelected to the Board.” Denton reported that this development had “lessened [Patterson’s] effectiveness.” After discussing perspectives given by two other speakers at the conference, Denton concluded by returning to Patterson, writing that Little Rock’s first Black school board member had emphasized to this gathering that “the wide differences in the problems of New York City and his own town are slowly fading. The city [of Little Rock] is becoming increasingly ‘ghettoized,’ he said. Ten years ago, Negroes were scattered throughout the city, but urban renewal has dislocated them and they are beginning to be concentrated in one section. And the whites have fled from the center of the city and resettled in suburbs.”

In the process of becoming both a resident and a historian of Little Rock, I have come to appreciate just how old, in a sense, Semuels’s story was when she reported it in 2016; just how sadly relevant Denton’s 1969 story remains; and just how little the general public today knows or cares about the facts reported in both stories. In particular, the narrative of residential re-segregation by way of so-called “urban renewal” is one that needs to be amplified. (Local public historian Acadia Roher’s recent StoryMap on this topic is an essential starting point for the Little Rock case, as is Brian Mitchell’s 2020 presentation on the West Rock community; next month’s Legacies & Lunch, by University of Arkansas PhD candidate Airic Hughes, will be equally crucial.) As my favorite writer, Ralph Ellison, wrote about his fellow Americans in 1964: “We’ve fled the past and trained ourselves to suppress, if not forget, troublesome details of the national memory, and a great part of our optimism, like our progress, has been bought at the cost of ignoring the processes through which we’ve arrived at any given moment in our national existence.” I do believe that Herbert Denton Jr. wholeheartedly felt this, too. And I think that he, like Ellison, was moved to become a writer in large part to combat such historical amnesia. Both men cared deeply about the moral implications and concrete necessities of remembering.

***

Denton’s 1969 piece was the first of five about Little Rock that he published in his lifetime. The next three appeared in the Washington Post in 1982: one news article in May, when seven of the Little Rock Nine reunited at Central High to commemorate the “bittersweet” 25th anniversary of 1957; another one in late August, about persistent “problems of race” at Central; and a meditative personal essay the following week in the Sunday Outlook section, titled “The Deeper Dilemmas of Little Rock.” There, Denton wrote, “In short, the blacks of Little Rock—a city that has become a national symbol of racial battles for others but which is hometown to me—are caught these days between many different worlds, feeling the tug of the past and uncertain of where they should go from here.”

Taken together, these three pieces from 1982 document an important moment in the evolution of both Little Rock’s racial realities and the city’s place in the United States’ story of race and democracy. It is not by coincidence that they appeared at the tail end of a two-and-a-half-year period that Denton spent covering the Reagan White House for the Post’s National staff. Denton would later criticize Reagan for “shift[ing] the burden of the debate onto blacks, thus assuring whites implicitly that they have done all that is required of them to eliminate racism and discrimination.”

That quote appeared in the fifth and final piece in which Denton wrote about Little Rock: “The Paradox of Change,” a book review of the revised edition of Racial Attitudes in America (by Howard Schuman, Charlotte Steeh, and Lawrence Bobo) for the spring 1986 issue of Nieman Reports. This time, Denton began with a personal memory, of listening to the radio on September 3, 1957, hearing President Eisenhower’s “annoyingly hesitant and equivocal” reaction to the events at Central High that day. “The old general’s rambling, tentative response made it sound as though his gut sympathies were as much with the howling white mob as the brave black students,” Denton wrote.

This opening memory lent both immediacy and legitimacy to Denton’s thesis: “A generation later, the inner conflict between the hearts of white Americans and the conscience of the nation that he expressed remains unresolved.” It provided the analytical foundation for a sweeping assessment of contemporary race relations in America, which Denton argued “are complicated even more by the national tendency to dissemble and lie when we talk about racial issues.…For most whites, issues of race tend to be pretty abstract, slipping on and off the screen. For blacks, race is a constant reality.”

***

As I’ve alluded to in this series of three Butler Banner posts (see Part 1 and Part 2), the act of rooting myself in Herbert Denton’s hometown while I research and write his biography has been crucial to understanding not only his personal and professional foundations, but also Little Rock’s vital place in the arc and process of American democracy. I am all too sad to report that most people my age, especially outside of Arkansas, have basically no notion of the place, let alone the actual details of its history—and that it’s taken me almost five years to return to and fully appreciate Alana Semuels’s Atlantic article.

My hope is that, as both Denton’s biographer and CALS’s in-house oral historian, I might begin to shine a public light on this history, in the same way that Denton himself surely would have, had he lived a longer life. The reason I’m writing about Denton’s five Little Rock pieces now is that they will provide the framework for a series of intimate, intergenerational discussions about Little Rock’s racial, cultural, and political history that I am preparing to convene this spring. By inviting childhood friends and neighbors of Herb’s to discuss the content, context, and contemporary resonances of these articles, along with younger activists and other informed interlocutors, my hope is that a coherent agenda and useful vocabulary for the Herbert Denton Community History Project might emerge and point some new ways forward.

Of course, the story of what happened here in 1957 needs to keep being told, especially as living memory of the event diminishes with each passing year. But this is just the trailhead. Little Rock, Arkansas, is—not was, is—one of this country’s most significant sites in its most abiding challenge: integration. There is so much more to probe; so many more dots to connect between this city’s past, present, and future; so many more avenues to open up for the American youngsters growing up here today.

I am grateful to Herbert Denton Jr. for leaving behind an incisive set of concise, accessible writings with which to start the discussion. I look forward to starting that work through CALS and reporting back soon.

By Benji de la Piedra, director of the Herbert Denton Community History Project, Central Arkansas Library System