calsfoundation@cals.org

Tending Memories for Future Generations

I didn’t know my grandfather. Every time I would ask about him, I’d hear a mix of responses: “Gong Gong was frugal.” “He loved ‘Edelweiss.’” “He gave a lot of lectures.” But my dad always said, “He was a great father.” And while I never knew him (he died several months after I was born), I have seen it. Gong Gong’s old film reels live on our laptops, phones, and social media.

One of the moments I have played over and over again is of my uncle and auntie attempting to climb Gong Gong while my dad, a five-year-old at the time, prepares to jump onto his back. Gong Gong just smiles and laughs as he struggles to find a way to hold on to all three of them. The film cuts to the next moment, showing my dad hanging off the back of his neck, my auntie swinging off of his right arm, and my uncle straddling his left hip. He looks so much like my dad when he smiles, it’s uncanny.

To have these memories in my pocket at all times is a pleasure, and one I don’t take for granted. Since I took the position at the Central Arkansas Library System as Memory Lab Coordinator—a job where I assist people in digitizing their home movies and family photos—my life has revolved around preserving these types of moments for everyone who visits the DIY Memory Lab.

With every appointment, I encourage people to take up the marathon that is archiving family photos and home movies by saying to them, “Future generations will thank you.” I don’t often get a chance to really delve into the significance of that statement, but it seems it’s at the forefront of everyone’s mind. For myself, having lost two family members in the past six months, encouraging people to work on their own personal archiving has become an intimately personal mission.

On my dad’s side of the family, I am the recipient of hundreds of photos and documents going back six generations from my family from China. In the case of my late family members, my Uncle Ted’s photos were largely already part of that digital collection. We had a paper trail of his life following when he met my Auntie Francis to the last family reunion he joined us for.

As for the second loss, the passing of my grandmother Ramona, my mother is the one who took on the responsibility of scanning her family photos for my granny’s funeral. Every day that she came into the lab with arms full of bags and boxes of photos, I could see her strategizing, like a marathon runner looking out past the starting line. This was a commitment of time, effort, and planning. But as I watched my mother carefully sort through photo frames, albums, and memory boxes, I understood each item to be a tether to her mother.

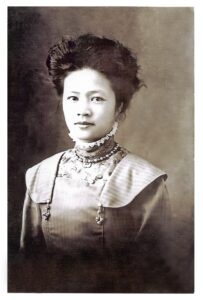

Your everyday items, photos, and videos that you may not see as valuable hold significance for the people in the generations following you. What I see in photos of my Popo as a twenty-five-year-old mirrors the features I see in my own face. The videos from my 2016 family reunion capture the last time I heard my late uncle play his famous rendition of “Danny Boy.” The recipe cards my granny left have her instructions for scalloped potatoes, a dish I’d ask her to make every visit, in looping cursive awfully similar to mine.

Through my own work archiving my family’s photos and home movies, I understand myself better in the context of the people who came before me. I get to add to this large collection, knowing that someone else decades later might have a deep appreciation and connection to the photos and videos I’m working to preserve now.

Digitizing is not a perfect storage solution, but it’s a comprehensive one. It’s an extra copy—a fail-safe in case of emergency. This is especially relevant in the wake of the wildfires in the Los Angeles area and other natural disasters that put physical items at risk. Hearing people mourn the loss of their homes and also grieve the loss of their family memorabilia is heartbreaking, and as many of us in Central Arkansas can attest to following the March 2023 tornado outbreak, natural disasters are hardly something you can completely prepare for, or even fathom, until they hit you.

The point of sharing this is not to cause a panic, but to remind us that the items we have stowed away in boxes in our closets and attics are precious. The work to preserve them is valuable. It can be tedious and frustrating, but it keeps your items alive for the young people like me who find connection and understanding in the family memories we’ve inherited. I urge you to do the work—run the marathon. Future generations will thank you.

***

If you would like to learn about the process of archiving your family memorabilia, please visit RobertsLibrary.org/PersonalArchiving to register for our free monthly Personal Archiving class. To make an appointment with the DIY Memory Lab, visit RobertsLibrary.org/MemoryLab.

By Meredith Li, CALS Memory Lab coordinator