calsfoundation@cals.org

The Best Time to Digitize? Today.

As a child of the 1990s, the VCR was the first piece of technology I learned to use on my own—for the single purpose of watching my favorite Blue’s Clues VHS tape. It was part of my everyday ritual to watch the big musical episode, sing along, and then rewind it to get it ready to play again the next day. (As evidence of how much I loved Blue’s Clues, my second birthday party was Blue’s Clues themed.)

It was a crushing blow, however, when I loaded my VHS tape one final time and witnessed a black screen cutting in and out of Periwinkle the Cat’s magic performance. This was the first time I understood that my beloved VHS tape was not indestructible. It had an expiration date, and the more I played Blue’s Big Musical, the more I hastened its destruction.

As technology developed and our family moved on from VHS to DVD to streaming, I completely forgot about VHS tapes and their limited lifespan. Then, early last year, my dad and I started the process of converting our old home movies into digital files, and this problem once again reared its head.

Our home movies had been a staple of my family’s inside jokes and dinner conversations for decades. One of our most famous was a movie we made called “Remote Control Katie.” In it, my sister Anna, about seven years old at the time, uses a remote to summon and “control” my other sister, Katie, about five years old, using a split screen and the best effects iMovie could offer in 1999.

We were shocked, however, when we tried to play our beloved tapes: many had broken audio, static, or sections that were completely blank. Of course, our tapes had been left in a plastic bin to collect dust in a closet with Christmas decorations and our broken DVD player for decades. We figured there would be some damage, but we never imagined there would be a day when we couldn’t relive some of those precious memories at all.

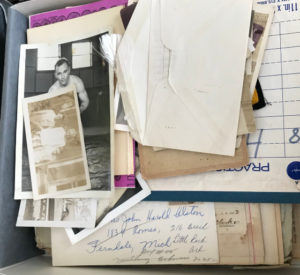

Since I’ve started my position as Memory Lab coordinator at the Central Arkansas Library System, assisting people with digitizing their home movies and family photos, I have started to see the severity of this issue. People come into the DIY Memory Lab with their old VHS tapes, expecting to relive a precious life event—their grandparents’ wedding, their kid’s first birthday, the last family reunion they had before a family member passed—only to find the tape has nothing left but static and broken audio. It’s devastating to lose those kinds of memories, and unfortunately, one I have witnessed over and over. Items like VHS tapes were not created with long-term preservation in mind, and they’re highly fragile and susceptible to mold. However, even if your VHS tape is in good shape, finding the equipment to play it on is another issue entirely.

In the past ten months that I have served as Memory Lab coordinator, I have experienced a slew of frustrations and challenges in making sure the equipment for digitizing is available to the public. In my first two months, our Betamax machine broke down. Even after tinkering with it, scouring the Internet for solutions to a problem that hasn’t been relevant for decades, and checking eBay hourly, it has been a near impossible task to offer Betamax appointments again. Two months later, our MiniDV player broke. Since then, three of our VCRs have stopped working for a variety of issues, and while finding a working VCR was much easier to accomplish, it took weeks to get things up and running again. These are the signs of the coming threat. VCRs were in nearly every home in the ’90s and early 2000s, but VCR repair has become something of a lost art form. Basic VCR repair and maintenance are no longer taught or generally offered at service shops. So, if you manage to find a working VCR, there is no guarantee you’ll be able to keep it working.

This is the dilemma we’re facing. This situation of both the physical media deteriorating and the equipment becoming obsolete is an imminent danger to our history recorded on analog media. This rapidly approaching threat, a phenomenon known as degralescence, is why the DIY Memory Lab is so heavily focused on digitization.

This is the dilemma we’re facing. This situation of both the physical media deteriorating and the equipment becoming obsolete is an imminent danger to our history recorded on analog media. This rapidly approaching threat, a phenomenon known as degralescence, is why the DIY Memory Lab is so heavily focused on digitization.

Digitization offers a way to keep and replay your memories in a way that does not damage the physical media or require the special equipment to play it. It is insurance. As part of the Memory Lab Network, we’re focused on combating the loss of personal history through what we call “good-ish practices.” Good-ish practices are methods of making personal archiving more accessible to the average person (rather than just archivists or specialists). Everyone’s history is worth saving; therefore, we believe in providing ways to preserve personal and family memories that are manageable so everyone can.

So, we do the work of finding and maintaining the equipment in order to provide a free and easy way to preserve your own personal history through digitization. We walk you through the whole personal archiving process to make sure you know how to keep your physical items and digital files safe. It can seem like an overwhelming task when you have a stack of bins full of home movies and photos, but this work needs to be done to combat the threat of degralescence that can wipe away our personal histories.

I have given an impassioned plea on this platform before, encouraging people to do the work, but now I am urging you to start the work, sooner rather than later. Because while those sweet memories will live on forever in my family’s inside jokes and dinner conversations, the tapes themselves will not.

***

If you would like to learn about the process of archiving your family memorabilia, visit RobertsLibrary.org/PersonalArchiving to watch an instructional video and/or register for our monthly Personal Archiving class; the next class is Thursday, April 24, noon-1:30 p.m. To make an appointment to use the DIY Memory Lab, visit RobertsLibrary.org/MemoryLab.

By Meredith Li, Memory Lab coordinator, Central Arkansas Library System