calsfoundation@cals.org

The Educated Smith Women of Tulip, the Athens of Arkansas

Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Arkansas’s women faced new challenges in adapting to the changes in their society as they moved from a largely French influenced society to one that was based in English Common Law. This shift took many rights away from women that they had previously enjoyed, such as independently operating businesses and owning land.

Still, there are many examples of women in Arkansas during the early statehood period who were able to receive an education and make an impact in their communities. Given the increasing free time available to white affluent women in the nineteenth century, they might have engaged in a variety of extra-domestic activities, including reading groups; church work; drama and debate clubs; singing ensembles; concerts; or benevolence associations such as those dedicated to temperance or assistance for the poor.

Still, there are many examples of women in Arkansas during the early statehood period who were able to receive an education and make an impact in their communities. Given the increasing free time available to white affluent women in the nineteenth century, they might have engaged in a variety of extra-domestic activities, including reading groups; church work; drama and debate clubs; singing ensembles; concerts; or benevolence associations such as those dedicated to temperance or assistance for the poor.

White women in Arkansas, as in the South generally, were somewhat educated in the antebellum period, but such attainment came with some difficulty, as Arkansas had no viable free education system for children. Schools did exist in Arkansas for those who could afford to pay to have their daughters educated: Springhill Female Academy in Hempstead County, Fayetteville Female Seminary, and the Ouachita Female Seminary in Tulip, Arkansas. Other prominent families might send their daughters out of state to receive an education, like the Smith family of Tulip.

In 1844, Colonel Maurice Smith journeyed from Fayette County, Tennessee, to Dallas County, Arkansas, with the hope of starting a new life for his family. Colonel Smith, a native of Caswell County, North Carolina, ventured into the recently created state with Dr. W. B. Langley and Cornelia Smith Langley, his son-in-law and daughter, as well as those they enslaved.

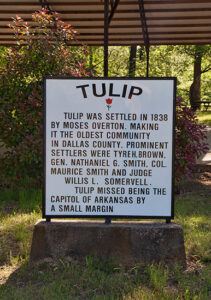

After Arkansas became a state in 1836, many people came from other areas in the South to settle in Tulip. For a time, the settlement was called Brownsville, after Tyre Harris Brown, and then Smithville, after Colonel Maurice Smith. The colonel reportedly said that the town should be called Tulip rather than Smithville, because “there are more tulip trees growing here than Smiths.” Tulip was described at the time as a cultured and wealthy community.

Dallas County was formed in 1845. Until this time, Tulip was part of Clark County. The 1850 federal census recorded in Smith Township “381 white males, 319 white females, 538 male negroes, and 458 female negroes”; all of the township’s Black residents listed were enslaved, as was the norm across Arkansas during the period. The Smith family themselves enslaved forty-four people between the ages of one and sixty-one in 1850.

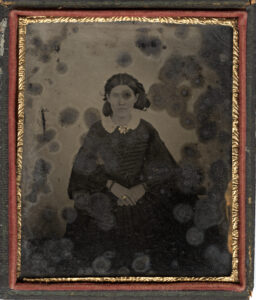

The Smiths left behind many letters, documents, and photographs depicting their rich life in antebellum Arkansas, available now to researchers as the Smith Family papers (BC.MSS.02.20). Many women in the family were very educated as indicated by the correspondence between one another. They were clued in to issues in agriculture, church, and community life within Tulip and throughout the state.

Clarissa Harlowe Reid Smith was Colonel Smith’s second wife. They had several children, but Annie was their only child to be educated out of state. The other children were likely educated in Tulip. George Douglass Alexander opened the Alexander Institute in Tulip in 1849. The following year, he brought in more teachers and divided the institute into two schools: the Arkansas Military Institute and the Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary, later the Ouachita Female Seminary. The town was known as the “Athens of Arkansas” due to this connection to education during the period.

Though these schools were available, Annie was educated at the Science Hill Female Academy in Shelbyville, Kentucky. The letters written to Annie while she was away at Science Hill are of particular interest and show how educated the women of the family were. Annie attended the academy in the late 1850s. Science Hill Academy was a revered school for women in the South during the period.

Additionally, as the correspondence in the collection indicates, the Smiths were devout Methodists, and during Science Hill’s early years it was operated by a Methodist minister and his wife, an educator. Science Hill was unique in its curriculum. It offered the typical courses a woman might be taught in an Arkansas female school like reading, writing, social graces, needlecrafts, and music; Clarissa Smith also endeavored to teach her students the sciences, something unheard of in those times.

While at Science Hill, Annie received letters from her family sharing updates on how the garden was faring, discussions of the growth of their congregation, and news about the work of itinerant Methodist ministers in Tulip, as well as fears about the state of the agricultural livelihoods in a time of unpredictable seasonal weather patterns and drought, something that resonates strongly with today’s Arkansans. Notably, in spring 1855, both Annie’s mother and Annie’s sister Elizabeth wrote of the harsh, dry winter and the late frost they had experienced and its impact on the corn crop and their garden. They were clearly aware of the effects of the dramatic weather patterns on their livelihoods.

There is also mention of them partaking in other work traditional for women of the time, such as sewing clothing for those they enslaved, gardening, cooking, and needlework. In one humorous mention, sister Elizabeth shared that their grandmother was “in the same spot” she had been in since Annie had left and was just “knitting away.”

After Annie finished her education at Science Hill, she returned home and married Felix Strong in 1859; they then moved to Malvern, Arkansas. In Malvern, Annie taught music to local girls, continuing the tradition of education.

***

Come visit us at the Research Room in the CALS Roberts Library to access the Smith papers or myriad other collections and other resources.

By Danielle Afsordeh, community outreach archivist, CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies/Roberts Library