calsfoundation@cals.org

A Story of Research…and of a Researcher

Guest post by Ron Fuller:

As a lover of history, member of the Arkansas History Commission, and occasional writer of historical articles, I have come to rely on the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Roberts Library to assist me with my research. Being somewhat old-school, I often find myself simply browsing the wonderful stacks in the Roberts Library Research Room covering a wide range of pertinent and historical topics. Yes, I occasionally use the great online resources offered by CALS, but in all honesty, I love turning the pages of antique books and holding in my hands the actual records, many of which were written hundreds of years ago. The wealth of information covering Arkansas places and people offers both the amateur and serious researcher a number of options, avenues, and supporting documentation needed for historical research. Not only can I find writings covering Territorial Arkansas, but also a wealth of information covering counties, people, places, and events. As I research topics for articles, I often find tremendous corroborating materials about how our ancestors lived, worked, and built this state I call home.

As a lover of history, member of the Arkansas History Commission, and occasional writer of historical articles, I have come to rely on the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Roberts Library to assist me with my research. Being somewhat old-school, I often find myself simply browsing the wonderful stacks in the Roberts Library Research Room covering a wide range of pertinent and historical topics. Yes, I occasionally use the great online resources offered by CALS, but in all honesty, I love turning the pages of antique books and holding in my hands the actual records, many of which were written hundreds of years ago. The wealth of information covering Arkansas places and people offers both the amateur and serious researcher a number of options, avenues, and supporting documentation needed for historical research. Not only can I find writings covering Territorial Arkansas, but also a wealth of information covering counties, people, places, and events. As I research topics for articles, I often find tremendous corroborating materials about how our ancestors lived, worked, and built this state I call home.

I have written a historical article for the Pulaski County Historical Review about the life of Captain Benjamin Shattuck, a little-known Arkansas transplant and pioneer who seemed to me a Jeremiah Johnson type, who showed up in Arkansas in the 1820s. He had served as a midshipman of the USS Constitution, disappeared for ten years, and ended up in Little Rock as the primary surveyor of the Cherokee Lands. He is buried in the William Woodruff plot at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock. My research at the Butler Center has also led me to write about 1820s Little Rock, which was a very tough place to call home, as well as several historical pieces about Hot Springs for the Garland County Historical Society’s journal The Record. I found a wealth of information for my AY magazine article on Dr. Fred Jones of Little Rock, a Black physician one generation removed from slavery who opened Little Rock’s first hospital, nursing school, and daycare for the city’s Black citizens, as well as building an insurance company. Thanks to the Butler Center and its resources, I even discovered and wrote about a murder and subsequent hanging that occurred in Pulaski County in 1835.

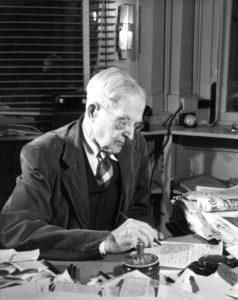

My use of Arkansas Gazette editor John Netherland Heiskell’s files, which are part of the limited use collection and owned by the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture, provided me with an almost unbelievable history of the Heiskell family and their importance to the state. Thanks to the help I received in the Research Room, I penned another article for AY magazine on John Netherland Heiskell’s son Carrick, who was lost piloting a C-46 transport during World War II while flying the infamous “Hump.” My research of the private Heiskell files led me to see the tenderness and humor of his famous editor father, often thought to be somewhat of an austere curmudgeon. Carrick and his entire family are resting at Mount Holly Cemetery.

I think researchers will greatly appreciate the staff and their knowledge not only of history, sources, and internet sites but also of genealogy. They can help with numerous sources one can use to find their family history. Thanks to the staff’s efforts, I even found the possibility of a Civil War Union officer in the direct line of a maternal grandmother. As I told the staff, it is a good thing my truly Southern born and bred great-grandmother has long since passed because she would find it most unpleasant to find a “Yankee” in our line. The staff and research at the Butler Center have also led me to documentation that enabled me to join the Sons of Union Civil War Veterans. The assistance provided has also saved me countless hours of additional research. I can tell you that their help and knowledge have saved me from a lot of deep genealogical rabbit holes and innumerable dead ends.

Preserving family history and that of our country and state should be something in which every family participates. We stand on the shoulders of a lot of hardworking and often brave ancestors who truly need to be remembered for what they did and for the state they built for all of us today.

I encourage anyone wishing to research history and genealogy to take advantage of the wonderful resources of the Butler Center and the expertise of their wonderful staff.

***

Profile by Steve Teske, CALS Butler Center/Roberts Library Research Services:

Ron Fuller had visited the research room in the Roberts Library several times before to find information of one kind or another. But this time was different. This time…it was personal.

Ron was seeking information about the grandfather he never knew. Ron’s mother and grandmother avoided speaking about the man. Ron knew that his grandfather had abandoned the family when his mother was a little girl. He knew that the same man had reappeared nearly fifty years later—now an elderly man dying of cancer—to ask forgiveness from Ron’s mother. Few words were said, aside from his mother’s assurance that she “didn’t have any bad feelings” about the man.

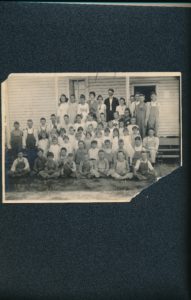

Ron had found a few traces of information about this missing ancestor. His grandmother had saved a photograph showing them in a group posing for a photo outside an Arkansas schoolhouse. He was in his twenties, the teacher at the school. She was a teenager, one of the fifty-some students in the school. A second photograph showed just the two of them, facing each other in a field. She was wearing a dark dress and holding a white lacy cloth. He was wearing a uniform from the United States Army, showing some involvement with the army around the time of the First World War.

Having done some research on his own, Ron knew that his mysterious grandfather, Clarence Veco Jones, is buried in the Huie Cemetery in Clinton, Arkansas. Buried with him is Veco’s second wife, Velma Jones. Nearby are the resting places of Veco’s parents, John L. Jones and Martha E. Jones. Further searching only muddled the issue. Veco—who later became an attorney—had boasted of serving in the war under General Pershing and of defending the Mexican border in 1917; on the other hand, available military records show him only serving as a medical orderly at Camp Pike near Little Rock, Arkansas, during World War I. Given Veco’s checkered history and the reticence of his grandmother, Ron began to wonder whether his grandparents had even been legally wed when his mother was born.

Ron brought his information and his questions to the Roberts Library. The Butler Center staff proved able to help. Searching records available in the research room, the staff uncovered evidence that Clarence Veco Jones and Lillian Dale Moss had been married July 5, 1918, in Yell County, Arkansas. The staff was then able to provide Ron with a copy of the marriage license from Yell County, taken from the Butler Center’s microfilm collection of county records.

Meanwhile, Ron also hoped to trace his lineage beyond his grandfather to learn more about his own roots and heritage. Cemetery information said that John L. Jones and his family had come to Arkansas from Tennessee; other records (including World War I records of Clarence Veco Jones) said that he had been born in Silver Point, Tennessee. John’s grave marker recorded his date of birth as February 28, 1857. Evidence pointed to two possibilities: one John L. Jones was born in eastern Tennessee around the right time, according to census records. Another John L. Jones was born in south-central Tennessee—the vicinity of Silver Point—but records showed that he was born in 1860, seemingly too late to be the John L. Jones who ended up in Clinton, Arkansas.

The eastern John L. Jones was born in Cocke County, Tennessee, to Allen Jones, a Civil War veteran. Allen Jones had served with Company H of the First Regiment, Tennessee Cavalry, on the side of the Union. Ron was excited by the possibility of a Union veteran in his ancestry—he is a member of the Sons of the American Revolution and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, but he would be delighted to belong to the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War as well. Sadly, the line leading from Allen Jones through John L. Jones to Clarence Veco Jones and thus to Ron was unprovable. This John L. Jones could not be shown to have come to Arkansas or to have lived at any time in Silver Point, Tennessee, where Clarence Veco Jones had been born.

The other John L. Jones proved to be far more interesting, and (what is more important) a better match to Ron’s family. He was born in Putnam County, Tennessee, to Alfred Moore Jones, one of the several sons of Bird Smith Jones. When the Civil War began, Bird Jones—then in his mid-fifties—was outspoken in favor of preserving the Union. His older sons, though, felt more tied to the Confederate movement. William Wade Jones and Prettyman Jones both joined Company F of the 25th Tennessee Infantry of the Confederate States of America, serving from July 1861 to August 1863. They were made officers of the Confederate army, but they somehow became dissatisfied with their place in the conflict. After deserting the Confederate forces, they joined their younger brother Alfred, enlisting in the Union army from Tennessee. Alfred enrolled as a private but was promoted to lieutenant before the end of the war. Wade and Prettyman both became captains in the First Tennessee Mounted Infantry of the United States. Alfred’s son John, born just before the war began, would move back and forth between Arkansas and Tennessee at the end of the nineteenth century. Some of his children were born in Arkansas; others—including Veco—were born in Tennessee.

Why the grave marker of Clarence Veco Jones states that he was born in 1857 rather than the correct 1860 remains unknown. This demonstrates a fact often found by historical researchers and genealogists: Even a piece of information carved in stone can be wrong. But Ron Fuller, with the help of the Butler Center staff, can now be content with a fuller account of his mysterious grandfather and of the family that produced that man who had seemed lost in the mist of time.