calsfoundation@cals.org

Beyond the Surface: Little Rock’s Unseen CCC Parkitecture

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Arkansas is best known for its work on state highways and parks during the Depression era. Lesser known is its municipal work.

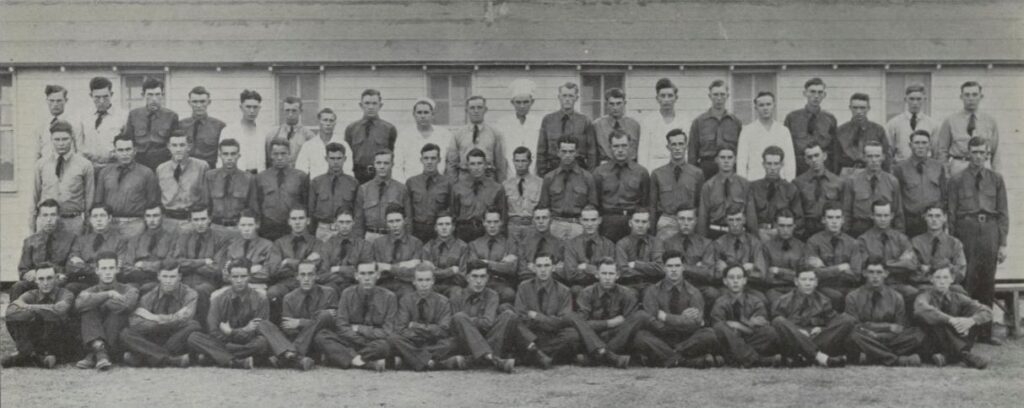

The CCC was created as the result of U.S. Senate Bill 8.598, which was signed into law on March 31, 1933. Those enrolled in the corps had to be between eighteen and twenty-five years old (later adjusted to seventeen through twenty-eight), United States citizens, of good moral character, out of school, and in need of employment. Enrollees could volunteer for a six-month period and reenroll each six months for up to two years. Later in 1933, separate camps were authorized for veterans of the Spanish-American War and World War I. Their duties were assigned according to their age and physical condition without restrictions on marital status or age. Arkansas had four veteran camps.

Most CCC projects in Arkansas were in national forests or on state-owned property. The young state parks system benefited greatly; the work program created roads, trails, lodges, cabins, campgrounds, amphitheaters, bathhouses, picnic pavilions, and beaches at six locations in four different regions of the state. In Little Rock, the CCC did municipal park work, primarily in Boyle Park.

Notably, Company 3777 of the CCC created trails and structures throughout Boyle Park. Prior to their work, the park was largely undeveloped. The structures employ the CCC’s famed “Parkitecture” style that would come to define their work nationally. Their work transformed these spaces and ensured their continued value to the city. This work is documented in their 1935 scrapbook located in the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies’ Arkansas State Parks Commission collection (BC.MSS.97.26).

Boyle Park was created in 1929. John F. Boyle (1874–1938) donated a 231-acre tract of land in the southwestern area of the city to the City of Little Rock with the stipulation that the land was to be allocated for recreational use. The park begins at 26th Street and Boyle Park Road, and Rock Creek runs through the park. Boyle Park was the third park of its kind in the city. It was preceded by MacArthur Park in downtown and Allsopp Park near midtown surrounded by the Hillcrest neighborhood.

The property that would become Boyle Park remained undeveloped until the 1930s due to the budgetary constraints created by the 1929 stock market crash. In 1933, the CCC Company 3777, under the direction of the State Parks Commission, created the Boyle Park project to help develop the land for the city’s recreational use. It is hard to say what drove this decision, as almost all the other CCC park infrastructure in the state is related to state parks rather than city parks.

Five buildings were constructed in Boyle Park in 1937: two pavilions, a spring house, a caretaker’s cabin, and a combination water tower/pump house/garage. Two culverts and a low-water bridge were also completed that year. The stones for these structures were brought in from Bear Den Mountain northwest of Little Rock. Signs were also created for the park by the CCC in collaboration with a blacksmith. The low water bridge, spring house, pavilions, and caretaker’s cabin still exist today. All that remains of the pump house are the stone walls and foundation. A modern roof was added to use the facility for storage.

The last major effort to rehabilitate the structures within the park was completed in 1994 after a bond issue allowed for funding. At the time, the Parks and Recreation department stated that the work would be all the improvement available for Boyle Park in the foreseeable future. The park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 22, 1995.

A Park Mystery

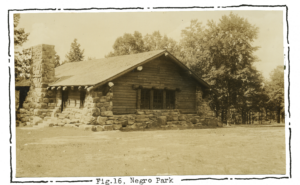

When exploring the scrapbook documenting Company 3777’s work in Boyle Park, I found a photograph of a structure labeled “Negro Park” on one of the final pages. An accompanying paragraph reads:

“We desire to mention that half a mile south of Boyle Park and not far from the Hot Springs Pike on ten acres of land formerly owned by the colored Sunday School Union but deeded by them to the State Park Commission our company has built a large recreational building for colored people. The building is constructed of large, weathered stone, logs, and rough sawn boards. The huge fireplace on the side of the building together with the stone foundation structure extending to the windowsills and on corners to the roof presents both beauty and permancy [permanency].”

Because of Company 3777’s prominent work developing Devil’s Den and Lake Catherine state parks, their work across the state is well documented. I had not previously seen mention, however, of any development of Black recreational areas by Company 3777—all the other spaces were restricted to use only by white citizens prior to integration. There was no other documented work by any CCC in Black recreational spaces in the state. It is possible that the development of the Watkins State Park, the Black state park noted in a 1941 WPA report on recreational facilities in Arkansas, was developed with federal aid, but it is very under documented and not clear that the park was ever truly developed at all.

Further, by the time the fight for a Black city park (what would eventually become Gillam Park) took shape in the late 1940s, the local Black newspaper, the Arkansas State Press cited that there were no publicly supported recreational facilities for Black residents in Little Rock. So, what is this structure called “Negro Park”?

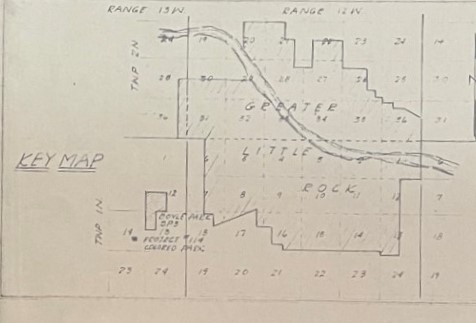

I reviewed a map from the same collection that showed the development of CCC structures in Boyle Park just in case it was noted. This key at the bottom right showed where this park might be located. I was able to compare this map to a modern section and township map of Little Rock and discovered that “West End / Union Park” was listed there. This seemed too coincidental knowing that the CCC Company noted that the land was donated by the Sunday School Union.

Little Rock’s Board of Directors’ minutes indicate that this was in fact the same site. The city annexed the area around the park in 1961 and acquired the deed to the park in 1967. In 2008, citizens of the John Barrow Neighborhood petitioned the city to change the name of the park from West End Park to Union Park in recognition of the Sunday School Union’s original donation. Additionally, in 2019, the city approved funding to build a pavilion at the park that would use as the foundation what was noted as the remains of a 1930s structure.

A survey of the property conducted in 2018 asserted that the structure was built by a WPA project, but this scrapbook indicates it was instead built by this CCC company in 1935. So, it is likely the only CCC park construction in the state created for Black residents. Unfortunately, the building burned sometime prior to 1961, though no documentation of the fire has been discovered.

Almost a century after the CCC completed its work, Boyle Park is primarily used by Little Rock’s residents as a place to bike and hike within the city. The trails are maintained by community volunteers, largely from the Central Arkansas Trail Alliance, and are used for walking, running, and mountain biking. Trail workers have rediscovered CCC contributions lost to time, including trailside fire pits. The pavilions created by the CCC are still in active use.

This is an excerpt of the research presented in “New Deal ‘Parkitecture’ in Little Rock” for Legacies & Lunch, July 5, 2023.

By Danielle Afsordeh, Community Outreach Archivist at the CALS Roberts Library/Butler Center for Arkansas Studies