calsfoundation@cals.org

From the Archives to the Community: Dunbar’s Rich Legacy

The neighborhood surrounding what now is Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior High School has historically been predominantly Black. Until the early twentieth century, when restricted additions began being developed in Little Rock, the city’s neighborhoods were not rigidly segregated by race, but certain areas such as the “East End,” the “South End,” and the neighborhood around Dunbar always were more Black than white. Situated within the Original City of Little Rock, the modern neighborhood’s boundaries are at West 9th Street, State Street, Roosevelt Road, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive.

Development in the area was driven by Little Rock’s early Black community. Structures date to the 1890s, and the area is commonly associated with the first free Black settlement in the city. The Dunbar neighborhood is also closely related to development in the West 9th Street business district.

However, the mid-twentieth century brought forth substantial changes through urban renewal programs, resulting in the demolition of many of the community’s historic houses, particularly the prevalent shotgun houses. Despite its historical significance, the landscape of the neighborhood today depicts a mix of post-1950s construction alongside remnants of its past, highlighting a blend of eras in its architecture and urban fabric.

The remaining historic homes were built by some of the most prominent members of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Black community in Little Rock. Because of these buildings’ significance, and the proximity to the city’s historically Black educational institutions, the Paul Laurence Dunbar School Neighborhood Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 27, 2013. This has led to a significant effort to rehabilitate the district’s historic properties and to promote the community’s history.

The Dunbar community is known for its association with prominent Black Arkansans, and several of the community’s residents impacted access to healthcare for Black citizens, including Dr. Fred T. Jones, Lena Lowe Jordan, and Frank B. Coffin. Black citizens did not have access to the same healthcare as white citizens during the early twentieth century primarily because there was no path to becoming a doctor for Black Arkansans without leaving the state for education.

Without the work of the following medical professionals, there would have been incredibly limited capacity for healthcare among Dunbar’s Black community:

Dr. Fred T. Jones Sr. was a trailblazer in establishing Black hospitals in Louisiana and Arkansas in the early twentieth century, offering crucial care to Black patients. Born in Homer, Louisiana, in 1877, he graduated from Arkansas Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) and later Meharry Medical College in 1905.

Dr. Fred T. Jones Sr. was a trailblazer in establishing Black hospitals in Louisiana and Arkansas in the early twentieth century, offering crucial care to Black patients. Born in Homer, Louisiana, in 1877, he graduated from Arkansas Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) and later Meharry Medical College in 1905.

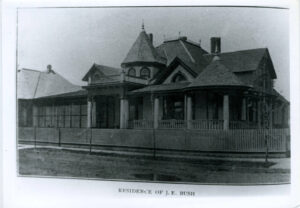

Facing limitations practicing medicine in Homer, he founded Mercy Sanitarium in Shreveport in 1915 and later opened the Booker T. Washington Memorial Hospital in Little Rock in 1918 (later named J. E. Bush Memorial Hospital). Jones introduced a new healthcare model for Arkansas’s Black community with the Great Southern Fraternal Hospital in 1919, pioneering the “hospital plan,” an affordable insurance concept.

After the founding of the Great Southern Hospital in Pine Bluff in 1932, locals responded with violent threats, and in response, Jones established the Southern Hospital Association in North Little Rock in 1938. He worked in North Little Rock until he died in 1938. He is buried in Haven of Rest Cemetery in Little Rock. In 1997, his family donated his personal records and photographs to the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, and we have those in the archival collection today.

Lena Lowe Jordan was a registered nurse and hospital administrator who managed two Black medical institutions and trained young Black nurses in Little Rock. After moving to the city in the 1920s with her husband Peach, she directed the Mosaic State Templars Hospital and later helped establish the Lena Jordan Hospital.

Lena Lowe Jordan was a registered nurse and hospital administrator who managed two Black medical institutions and trained young Black nurses in Little Rock. After moving to the city in the 1920s with her husband Peach, she directed the Mosaic State Templars Hospital and later helped establish the Lena Jordan Hospital.

The hospital, offering diverse medical services, was open to all Black patients regardless of their ability to pay. Jordan initiated a pioneering nurse training program and worked tirelessly for thirty years caring for the underserved Black community in Little Rock.

She died on September 30, 1950, and is buried at Haven of Rest in Little Rock. Her former residence at 2424 Ringo Street is now a vacant lot.

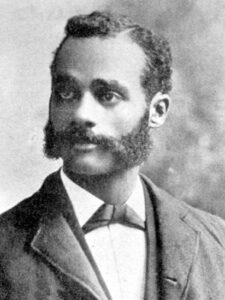

Frank B. Coffin, born on January 12, 1870, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, attended Rust College and earned degrees from Fisk University and Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. He moved to Little Rock in 1895 and obtained a license to practice pharmacy in Arkansas after passing the necessary exam and worked in the pharmacy business at George E. Jones Drug Company at 700 West 9th Street.

Frank B. Coffin, born on January 12, 1870, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, attended Rust College and earned degrees from Fisk University and Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. He moved to Little Rock in 1895 and obtained a license to practice pharmacy in Arkansas after passing the necessary exam and worked in the pharmacy business at George E. Jones Drug Company at 700 West 9th Street.

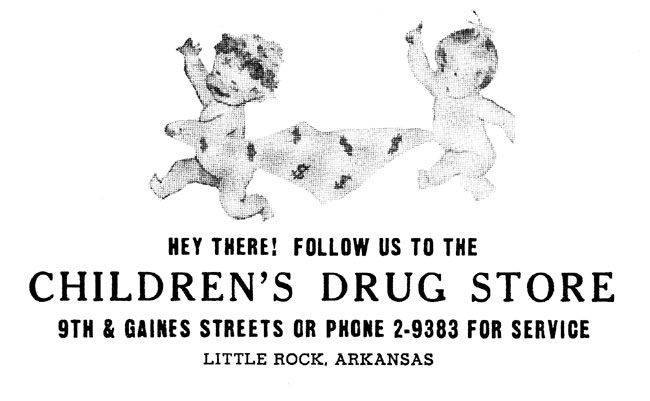

On January 1, 1898, Coffin purchased the business and became the sole proprietor, owning the Children’s Drug Store by 1928. Coffin was known for tutoring kids in the community and for his store’s popularity with children due to a soda fountain and candy.

Coffin married twice and lived at 1118 Izard Street. The site of his home is now part of Philander Smith University. Coffin wrote poetry reflecting his love for children and his mother, and discussing racism and his admiration for figures like Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln. He died on March 4, 1951, at United Friends Hospital, with funeral arrangements by United Friends Undertakers. The United Friends, whose motto was “We Serve In Life, We Serve In Death,” provided insurance, hospitalization, and funeral arrangements for its members.

***

The accomplishments of these three individuals offer a glimpse into how Dunbar’s residents have influenced not only Little Rock but also the broader Arkansas Black community. Today, the neighborhood stands as a testament to the resilience, achievements, and enduring legacy of the Black community in Little Rock.

By Danielle Afsordeh, community outreach archivist at the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies/Roberts Library