calsfoundation@cals.org

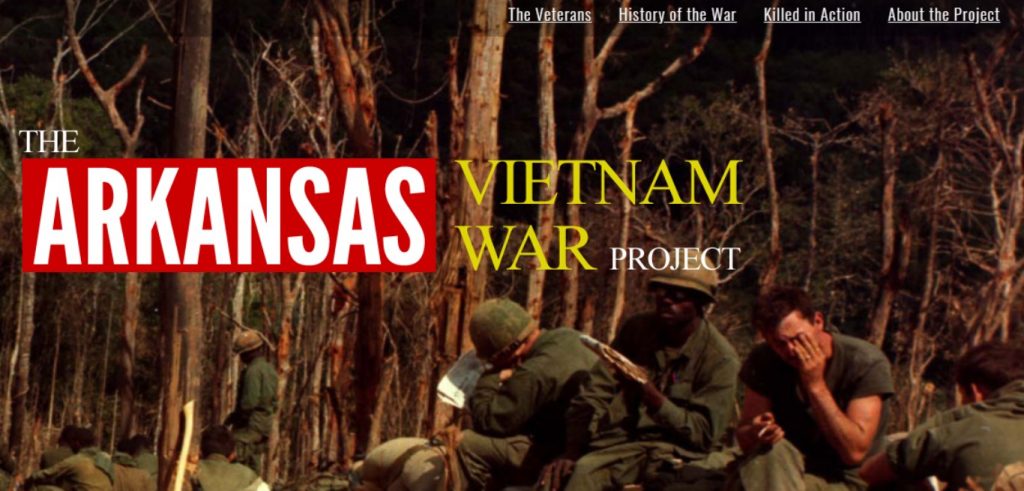

Honoring Vietnam Veterans: Seeking Stories from Women and Men Who Served

For American Baby Boomers and Generation Xers, the Vietnam War was a major part of cultural consciousness. Filmmakers and musicians explored the war and its aftershocks throughout the 1970s and 1980s as the ongoing emotional difficulties faced by many Vietnam veterans gave rise to a new medical term: PTSD. But as three more decades rolled by, the immediacy of the Vietnam War experience melted away.

For American Baby Boomers and Generation Xers, the Vietnam War was a major part of cultural consciousness. Filmmakers and musicians explored the war and its aftershocks throughout the 1970s and 1980s as the ongoing emotional difficulties faced by many Vietnam veterans gave rise to a new medical term: PTSD. But as three more decades rolled by, the immediacy of the Vietnam War experience melted away.

As we now begin to lose our Vietnam veterans to age and illness, many of the individual stories that define the experience of the Vietnam War are at risk of vanishing with them. But that doesn’t have to happen: recorded oral histories are a way to make sure that those voices will still tell their stories to later generations. The Arkansas Vietnam War Project was started in 2015 with a mission to preserve the oral histories, photographs, and documents of Arkansas residents who had served in the war.

Over 50 veterans with Arkansas connections have now told their personal stories to archivist Brian Robertson of the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Those stories are available to the public online, providing a wide array of memories and perspectives from different branches of the military.

Robertson believes all the participants have added value and interest to the project.

“One of the things I’ve heard when I ask people to tell their stories,” Robertson said, “is that a lot of guys will respond by saying, ‘I wasn’t John Wayne—my job wasn’t that important.’” Robertson tries to convey to veterans that the exact nature of one’s military service does not make it more or less significant: “You were there and you were contributing, whether you were a guy going through the jungle with a pack on his back, or you were on a base somewhere far from the fight. And I think it’s important to capture a cross-section, not just the guys on the ground.”

Robertson finds that one essential truth seems to take hold as veterans consider recording their stories. “I always say, ‘Well, if you don’t tell your story, nobody else will.’ And that seems to resonate.”

The project still actively seeks testimony from Vietnam veterans, and Robertson would especially like to interview more women. “I’ve gone to great lengths to try to track down some of the women who were over there, but I’ve come up empty every time,” Robertson said. “Because Arkansas is a small state, percentage-wise there would have been dramatically fewer women compared to the men, especially since there were far fewer women over there to begin with. But I know there must be some women out there, whether they were nurses or Donut Dollies working for the Red Cross.”

Robertson has found that both the veterans and their family members are very glad to have the oral histories on the record once they are completed. “I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve heard from family members saying, ‘Oh, I’m so glad you did this interview with Dad or Granddad. If you hadn’t recorded these stories, we would never have heard them.’”

“In a lot of ways, this material is family history,” Robertson said. “You do have the broader context of the Vietnam War, but you can also drill all the way down and it becomes family history. And we always give copies of the interview to the veteran, and if they want additional copies for their family, they can have those too.

The veterans are also conscious of the way their stories may help future generations once they are recorded.

Steve Brackins, who was a U.S. Marine aviator in the early years of the war, sees a very timely lesson that younger people might take away from America’s involvement in Vietnam.

“I think down the road, if a 9th grader working on a Civics project should be cruising along and see from a different perspective, instead of a textbook, it’s worth it,” Brackins said. “I think the moral of the story is to be informed and vote your convictions. Don’t think it ain’t gonna happen to you, because suddenly, you’ll find you’re involved in something that you thought was just politics. Just like the [2020] coronavirus.”

Brackins also thinks the stories are helpful for other veterans. “I did get a text message from a fellow Vietnam vet aviator who saw my interview and wanted to thank me for doing it.”

Brackins finds a teachable principle even in one of the most painful aspects of the war for veterans: the negative behavior of some Americans toward those who served in the military.

“I think the protests were a good thing even though a lot of vets think they were a bad thing. It was good that the young people got involved. The problem is that they didn’t go after the politicians—they went after the soldiers. And I think we’ve learned that lesson. A good demonstration against the war would have been against the politicians, not the soldiers. Politics—it’s a wicked thing.”

Jim Marsh gave an interview from his perspective serving as a combat demolition specialist in the U.S. Army Infantry. He also appreciates the work of the project. “I was encouraged that the history was being recorded before everybody died without leaving records. It’s great capturing things that could be lost in another decade,” Marsh said. “And it’s an opportunity to create a platform for people to say what they wanted to say, especially for people who haven’t had a chance until now to work through the problems. There were half a million people over there, which means half a million different problems depending on their experiences. Verbalizing things helps, and could be therapeutic.”

Marsh both observed and personally experienced the benefits of working through the war’s trauma by telling stories. “I was from New York, and the culture I came from tended to be guarded with some paranoia. The message I received when I came back was that you hang up your uniform and you don’t talk about it. But while I was in Vietnam, I met a whole group of people from Southern California who were well-adjusted, happy people. And after they got back, those Southern California guys started meeting and talking about their war experiences right away. They kept meeting together for 40 years, but I didn’t know about it until I met them at our reunion. That was healing for me to see, that they all came through it as well-adjusted people because they talked about it.”

Marsh also came through without lasting psychological trauma because he found his own way to tell his story. “For me, whatever hang-ups I had, I had also worked through, and that’s because I started journaling when I came back. To this day, 50 years later, I’ve journaled. If I didn’t feel good, I’d write it down and be as honest as I could, and that was very therapeutic.”

Bill Luplow, U.S. Marine aviator, had a chance to voice his opinion on the war through the interview.

“A lot of things I saw really upset me because I thought Lyndon Johnson had that war for his own benefit, because his family made millions,” Luplow said. “Lyndon Johnson called the shots, and he didn’t give a damn about who was there and who lived and died. I lost some good friends and all for nothing.”

But even though Luplow felt the war was a terrible mistake, the experience of recording his story was positive. “It’s good to have for posterity, so some folks who haven’t even been born yet can refer back to it and find out things they never knew about the war. And it’s good to remember all the people who didn’t come back.”

Archivist Robertson sees the overall value of the contribution each person has made by telling a story for the Arkansas Vietnam War Project. “It’s one thing to read about Vietnam from a secondary source, and it’s another to hear it from someone who was actually there,” Robertson said. “The oral history makes it more real because you’re hearing from someone who experienced it firsthand.”

The ongoing Arkansas Vietnam War Project seeks to honor veterans and their contributions to the war effort. If you served in Vietnam in any capacity or know someone who did, male or female, please consider contacting Brian Robertson at (501) 320-5723 or brianr@cals.org to begin the simple interview process. You can view samples of other veterans’ oral histories here.

Feature by Rosslyn Elliott, Creative Writer, Central Arkansas Library System