calsfoundation@cals.org

The Root Systems of History

My long-suffering colleague Ali Welky, who manages the Roberts Library and Encyclopedia of Arkansas blogs, occasionally complains that my own contributions here too often take the form of rambling ruminations upon some book I’ve recently read that take a long time to tie back into the work we do at the EOA, and sometimes tie in rather indirectly.

So to mix things up a bit, I’m going to do something different this time around. I’m going to reflect back upon two books I’ve recently read. Because I am a dynamic individual fully capable of embracing change.

But actually, these books, both studies of the life and work of relatively contemporary European philosophers, have quite a bit to say about the use and abuse of heritage as a concept, and as we are arguably part of the heritage industry here in Arkansas, we need to be aware of the issues that arise when contemplating what it means to have, or to set down, roots.

The first book is The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas by Robert Zaretsky. Simone Weil had the sort of life that is hard to describe using shorthand terms, for she was a philosopher, activist, worker, rebel, mystic, and more. Most of her work was published after her death in 1943, including The Need for Roots (1949). In this work, Weil levied immense criticism at modern societies and the sense of déracinement (uprootedness) that they produce. This uprootedness was not simply the mobility that our societies offer to individuals now able to seek life and joy outside their natal home, but more a breaking of social and psychological bonds between people, the reduction of human relationships to simple transactions, so that one can experience uprootedness without ever having left the village where one was born. The consequences of all of this, writes Zaretsky, “are a catastrophe to which we have grown accustomed, being taught to embrace ends, not means; to see others as objects, not subjects; and to accept what Weil calls idolatry, and forget the integrity that once defined our relationship to our work and ourselves.”

The first book is The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas by Robert Zaretsky. Simone Weil had the sort of life that is hard to describe using shorthand terms, for she was a philosopher, activist, worker, rebel, mystic, and more. Most of her work was published after her death in 1943, including The Need for Roots (1949). In this work, Weil levied immense criticism at modern societies and the sense of déracinement (uprootedness) that they produce. This uprootedness was not simply the mobility that our societies offer to individuals now able to seek life and joy outside their natal home, but more a breaking of social and psychological bonds between people, the reduction of human relationships to simple transactions, so that one can experience uprootedness without ever having left the village where one was born. The consequences of all of this, writes Zaretsky, “are a catastrophe to which we have grown accustomed, being taught to embrace ends, not means; to see others as objects, not subjects; and to accept what Weil calls idolatry, and forget the integrity that once defined our relationship to our work and ourselves.”

By contrast, Zaretsky writes, “rootedness in a finite and flawed community is the basis for a moral and intellectual life that strives to overcome” the limits imposed by a past that contained indefensible actions on the part of a community. Weil does not shrug off responsibility for past atrocities but insists that what is honorable and virtuous about the community must be carried forward, that the community, the bond it offers people, is, far beyond individual human rights, the basis for true justice.

Another philosopher concerned about roots was Martin Heidegger, a German existentialist whose legacy has increasingly come under scrutiny not simply for his involvement in the Nazi Party but also how his philosophy appears to promote certain notions to which the Nazis were attracted, as explicated expertly by Richard Wolin in Heidegger in Ruins: Between Philosophy and Ideology. As Wolin writes, “For Heidegger, ‘originary thinking’ (anfängliches Denken) meant ‘bodenständiges Deken’: a thinking that was rooted-in-soil. Conversely, Heidegger consistently condemned intellectual paradigms that shunned ‘rootedness’ as nihilistic and degenerative, insofar as they abetted the technological mastery of Being and beings.” So far, Heidegger’s idea of “ontological rootedness” sounds like it might parallel Weil’s concerns vis-à-vis modern society’s promotion of “uprootedness,” especially as regards Heidegger’s condemnation of the “destabilization and loss of identity associated with the transition from Gemeinschaft [community] to Gesellschaft [society].”

However, one should perhaps proceed with caution before embracing a German lambasting modern society, because yes indeed, Heidegger’s concern for roots extended to the people who best exemplified those roots, the German Volk, and were used to render as alien people deemed to lack sufficient roots. As Wolin writes, “Heidegger regarded Jewish ‘rootlessness’ as an emblem of Jewish perdition: an ontological stain that permanently consigned the Jewish people to ‘inauthenticity,’ insofar as Heidegger embraced ‘rootedness’ as a sine qua non for ‘authenticity.’”

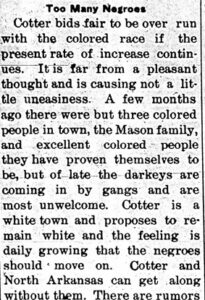

The idea of roots, it appears, can be far too easily employed to deny others their own roots in soil you might want to consider a more exclusive domain. After all, many Europeans justified the extirpation of Native Americans and theft of their land by describing those natives as “rootless” nomads—a particularly ironic accusation on the part of people who ventured halfway across the globe, a distance that would have put any nomadic tribe to shame. The Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s was a nativist, and specifically anti-Catholic, political party that sought to preserve economic opportunities for “real” Americans. (Note, the United States of America had not even existed a full century at this point.) However, this was by no means the end of rhetoric claiming that there existed some essential “real America” from which strangers can and must be excluded. And it often had little to do with actual duration in this land, or many of the people who carried out the acts of racial cleansing that produced “sundown towns” would, themselves, have been driven out, given that many of these towns were boomtowns, and many of the people who moved there, both Black and white, were relative newcomers.

The idea of roots, it appears, can be far too easily employed to deny others their own roots in soil you might want to consider a more exclusive domain. After all, many Europeans justified the extirpation of Native Americans and theft of their land by describing those natives as “rootless” nomads—a particularly ironic accusation on the part of people who ventured halfway across the globe, a distance that would have put any nomadic tribe to shame. The Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s was a nativist, and specifically anti-Catholic, political party that sought to preserve economic opportunities for “real” Americans. (Note, the United States of America had not even existed a full century at this point.) However, this was by no means the end of rhetoric claiming that there existed some essential “real America” from which strangers can and must be excluded. And it often had little to do with actual duration in this land, or many of the people who carried out the acts of racial cleansing that produced “sundown towns” would, themselves, have been driven out, given that many of these towns were boomtowns, and many of the people who moved there, both Black and white, were relative newcomers.

So does this mean that, contra Weil, the idea of rootedness is inherently reactionary? The back-to-the-land movement might stand as a counterpoint to that, especially as many participants actively sought to create those smaller, more tight-knit communities that Weil regarded as the source and summit of human nurturing. Folks who are part of the bioregionalism movement extend the concept of rootedness, of community, beyond the human species to include all species and those sources of water, air, and food that make our lives, all of our lives, so possible. It’s a radical concept, etymologically speaking.

Rootedness, it seems, is rather like the concept of freedom, given that it represents something of true value and worth but can be employed rhetorically to deny itself. “Freedom Is Slavery” in George Orwell’s 1984, and rootedness was inauthenticity, at least according to Heidegger’s view of the Jews as a group.

The problem is that we don’t seem to appreciate the variety of root systems that abound in this world. I have in my backyard a fig tree. These have rather famously deep taproots. In my mother-in-law’s yard is a big grove of cane. This has a rhizome dependent system of shallower roots, but the cane grows tall because it constitutes a network of culms that shield and reinforce each other. The kind of roots one needs depends upon the local environment and what one is trying to achieve.

And so it is, I believe, with human communities. Simone Weil famously lamented radio and how it acted as a solvent on local communities, so we might imagine what she would have made of mass media such as television and, later, the internet. These things make it possible to live a life largely divorced from one’s surroundings. But, in contrast, I have also heard from a number of recent transplants to Arkansas who were delighted to find the Encyclopedia of Arkansas online, delighted to have access to information about their new town and their new neighbors they would, in a previous era, have been denied.

Roots are what you make them. Having a root system doesn’t just leave you settled or fixed. Roots are one of the means by which a plant explores its environment and finds nutrition. And if the environment is too hostile, not even the best root system will keep it alive.

Where are your roots? I don’t just mean where you were born or from what line of people you descend, but rather—what allows you to flourish? And does a sense of history play any role at all in that?

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas